Why Probiotics Are Good For You And Your Dog

Trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi live on or inside of us. Maintaining a balanced relationship with them is to ours, and our pet’s advantage. Together they form the gut microbiome; a rich ecosystem that performs a variety of functions in the body. These bacteria can digest food, produce important nutrients, regulate the immune system and protect against harmful pathogens. A range of bacterial species is necessary for a healthy microbiome, but there are many things that affect our microbiome, including the environment, medications like antibiotics, and even the method of delivery when our pets were born. Diet is emerging as one of the biggest influences on the health of our gut, and subsequently our overall health. Whilst we can’t control everything that influences the composition of our gut, we can pay attention to what we eat.

And probiotics are one of those things.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that provide health benefits to the host when ingested in adequate amounts. They are not to be confused with prebiotics which are selectively fermented ingredients that result in specific changes in the composition and/or activity of the gut microbiota. Synbiotics are products that contain both.

The term probiotics was first introduced in 1965; in contrast to antibiotics, probiotics are deemed to stimulate growth of other organisms (antibiotics are used to kill).

Probiotics are live microbes that can be formulated into many different types of products from food to supplements. The most common probiotics you’ve come across will likely be lactobacillus and bifidobacterium.

Probiotics are reported to suppress diarrhoea, alleviate lactose intolerance (in humans), exhibit antimicrobial activities, reduce irritable bowel symptoms and prevent inflammatory bowel disease.

With a rap sheet like that, we need to explore these functions in a little more detail.

Probiotics in Gut Barrier Health

The intestine possesses a barrier. It acts as a selectively permeable barrier permitting the absorption of nutrients, electrolytes and water but providing an effective defence against toxins and antigens. This barrier consists of a mucosal layer, antimicrobial peptides, and tight junctions.

The mucosal layer has an important role in regulating the severity of infections. An altered mucosal integrity is generally associated with inflammatory bowel disease. There is evidence that certain strains of the commonly deemed bad, Escherichia coli can prevent the disruption of the mucosal layer and can in fact, restore it when damaged.

Mucin glycoproteins are large components of epithelial mucus and several lactobacillus species have been seen to increase mucin production in humans. This mucin is key in preventing the adhesion of potential pathogens in the gut.

Probiotic microorganisms expressing antimicrobial peptides could also be efficient in bacterial control.

Tight junctions are key to barrier formation and certain strains of bacteria, lactobacilli for example, modulate the regulation of several genes encoding adherens junction proteins. The gut is maintained by the expression of both adherens junction and tight junction proteins.

There are also links between inflammation and intestinal permeability. Certain probiotics have been seen to prevent cytokine-induced epithelial damage.

Competitive Microorganisms

A healthy gut is when the balance is tipped in favour of the good bugs. The issue is that every microorganism’s purpose in life is to survive. To survive in the intestinal tract, species must compete for receptor sites. To do this,they have a few tricks up their sleeve. Species will create a hostile environment for other species, they will eliminate receptor sites, produce, and secrete antimicrobial substances and deplete essential nutrients other species need to survive. Lactobacilli and bifidobacterial have been shown to inhibit a range of pathogens including E. coli, Salmonella, Helicobacter pylori and Listeria.

Gastrointestinal Disorders where probiotics have shown benefit:

- Antibiotic associated diarrhoea– several randomised controlled trials have demonstrated AAD may be prevented by administration of probiotics.

- Colitis – Studies are somewhat inconclusive, but it is recommended to follow antibiotic treatment in these cases, with a course of probiotics.

- Infectious diarrhoea-significantly shortened using probiotics.

- IBS – Bifidobacterium demonstrates significant effect in reducing IBS symptoms.

Probiotics and the Immune System

Probiotics play a role in the delicate balance between necessary and excessive defence mechanisms in the innate and adaptive immune systems.

One mechanism in which they do this is through gene expression. Certain strains of bacteria have been seen to regulate genes mediating immune responses. It was clear that the administration of certain strains modulated inflammation (L. acidophilus), wound healing,cellular growth, proliferation, and development (L. Rhamnosus).

Other strains of bacteria have been seen to modulate Th1 and Th2 balance. These are cytokines which are hormonal messengers, responsible for most of the biological effects in the immune system. Th1 cytokines tend to produce inflammatory responses, responsible for killing intracellular parasites and for perpetuating autoimmune responses. However, excessive inflammatory responses can lead to tissue damage, so it needs to be balanced. This is where Th2 cytokines come in. Th2 include interleukins which have more anti-inflammatory responses. Th2responses help regulate Th1 responses.

The importance of immune modulation at a gut level can be understood easily when you consider that approximately 70% of the entire immune system is found here and the thin layer of connective tissue known as the lamina propria contains around 80% of all plasma cells responsible for IgA antibody production (IgA is the first line of defence in the resistance against infection).

Not only that but several bacterial strains are known to synthesise vitamins. Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus are known to synthesise thiamine, folate, biotin, riboflavin, pantothenic acid and vitamin K. Not only that, but bacteria play a role in their absorption!

Probiotics and Obesity

Gut microbes play a major role in the energy extraction from food, through a variety of mechanisms.

Many plant polysaccharides and complex carbohydrates cannot be digested by the host; however, the gut microbes can metabolise them to short chain fatty acids like acetate, butyrate and propionate. Butyrate provides an energy source for colonic epithelial cells and also plays an important role in modulating immune and inflammatory responses. There are also reports that butyrate improves glucose homeostasis; alleviating insulin resistance and diet-induced obesity.

Acetate has received particular attention for its role in appetite regulation. In cases of increased fermentable carbohydrates, there is a reduced energy intake and weight gain.

However, in the same strand, studies have demonstrated that the amount of SCFA’s can be higher in obese individuals; suggesting that SCFAs can be assimilated into host carbohydrates and lipids. This further suggests a wider view needs to be taken when assessing particular health concerns.

The microbiota of obese animals is different to that of their lean counterparts, but studies have only demonstrated strain specific effects of probiotic use; some beneficial, some deleterious.

Probiotics and Behaviour

We can thank the many studies carried out on germ free mice for these revelations. The gut affects behaviour though this thing called the gut-brain axis.

Studies have shown, that when born and raised in sterile environments, mice developed abnormal amygdalas, with very unusual neurochemistry. The amygdala is a part of the brain most often referenced as the fear centre. It processes many emotions and plays a role in behaviour, especially aggression. Abnormal amygdala function has often been linked to anxiety and depression. Not only that but germ-free mice demonstrate unusual hippocampal development, which is a part of the brain essential in memory formation and learning. Both the amygdala and hippocampus are structures in the limbic system of the brain, which has a role regulating the functioning of the autonomic nervous system. And the ANS is one of the major neural pathways activated by stress. n short, bugs can affect our stress response too!

Going full circle, stress also alters the microbiome which can lead to increase inflammation.

Studies have demonstrated that during times of stress, bacterial colonies change, some increase, some decrease. Most often, protective bacteria decrease. Not only that but levels of short chain fatty acids decrease in times of stress too.

This isn’t greatly surprising when we consider that the sympathetic system diverts blood to limbs and the brain in order to deal with the threat. The parasympathetic system restores flow to the digestive system, but here the stressor needs to have passed. In chronic stress, the stressor never seems to pass.

The microbiome also appears to affect myelination, having a role in the development and function of the central nervous system. Changes in myelin abundance have regularly been linked with neuropsychiatric disorders. It has been strongly concluded that appropriate cortical myelination relies on the presence of a functional microbiota during windows of critical brain development.

Bacteria have been shown to produce and/or consume neurotransmitters including dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, and GABA.

Dopamine is one of the major neurotransmitters in reward-motivated behaviour and is a precursor for norepinephrine and epinephrine. Norepinephrine is known for its role in alertness and arousal, along with memory learning and attention. Certain strains of bacteria like Escherichia Coli have an increased growth rate in the presence of dopamine, where other bacteria like Bacillus cereus, produce dopamine.

In germ free animals, levels of serotonin are significantly reduced; serotonin whilst having a range of biological functions, contributes to overall well-being and general feelings of happiness. In recolonisation with spore-forming species, levels can be restored.

GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system. Altered GABA neurotransmission is often associated with sleep disorders, behavioural issues, and chronic pain. Not only that but it can disrupt intestinal motility and acid secretion. Bacteria can consume and produce GABA. Germ free animals have regularly demonstrated low levels of GABA; the most referenced bacteria to produce it are Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium. Interestingly, a predominantly keto diet has been shown to increase GABA levels too.

Probiotics and Respiratory Health

With their role in immune system function, it’s not surprising that reviews have demonstrated beneficial effects of supplemental probiotics in respiratory health, particularly Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains. When supplemented alongside Vitamin C in humans, there is a significant reduction in acute respiratory infections, in otherwise healthy subjects.

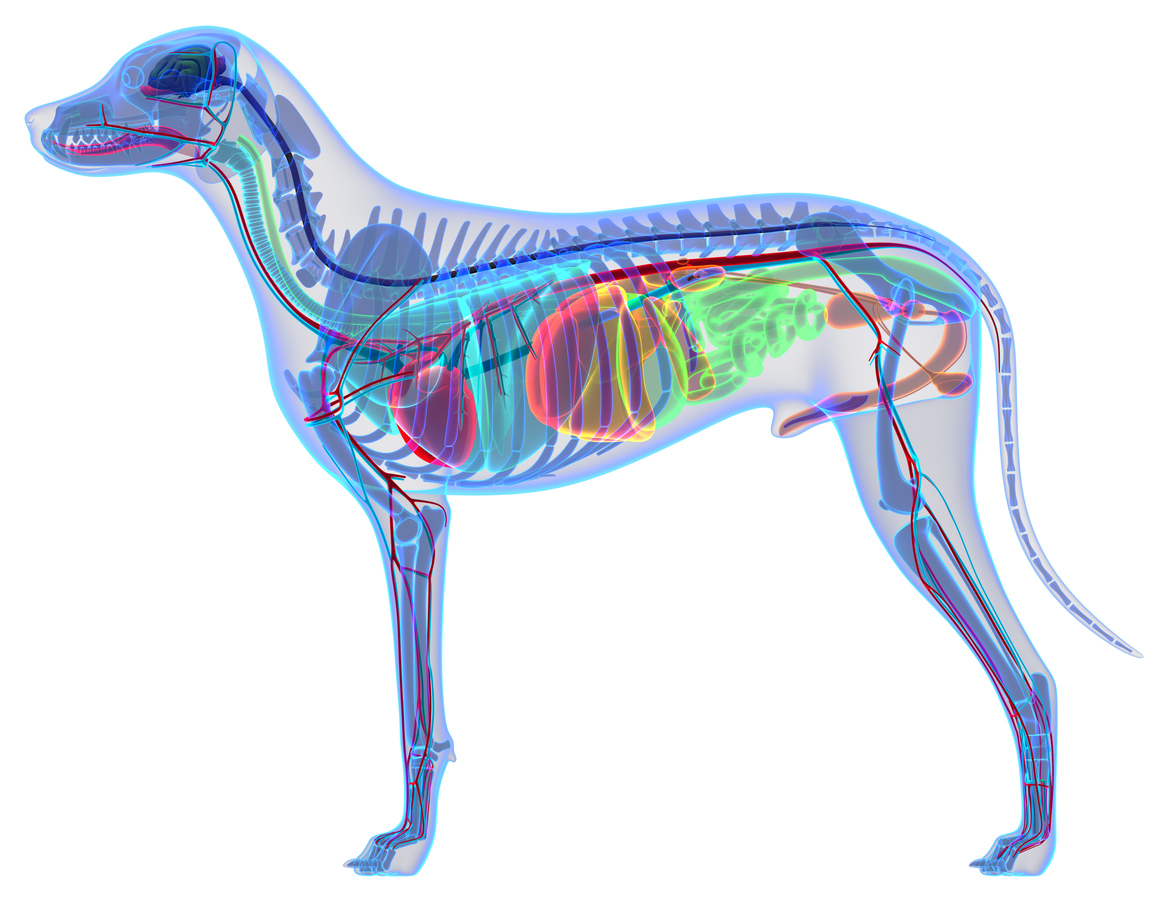

Probiotics and Dogs

There is less known about the canine microbiome. The predominant species found in the canine microbiome are helicobacter and lactobacillus spp. The healthy canine microbial community consists of firmicutes, proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, spirochaetes, fusobacteria and actinobacteria.

All animals have the same 6 bacteria phyla (or families) in their guts. These phlya make up 99% of all of the gut bacteria and are made of the following:

- Firmicutes (46.4% of obtained 16S rRNA gene sequences)

- Proteobacteria (26.6%)

- Bacteroidetes (11.2%)

- Spirochaetes (10.3%)

- Fusobacteria (3.6%)

- Actinobacteria (1%)

Distribution of bacterial phyla in the duodenum of 14 dogs with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and six healthy dogs

Non‐specific alterations of the GI microbiota have been regarded as a pivotal factor for the development of acute or chronic GI disease in disease based on findings. It is clear that in times of disease, the composition of the microbiome is significantly changed and can lead to disease.

This is where the call for probiotics comes in.

To date four bacterial strains have been examined by the European Food Safety Authority for their safety and efficacy as probiotics for dogs:

- Enterococcus faecium (two strains)

- Lactobaciullus acidophilus

- Bifidobacterium animalis

However, Lactobacillus rhamnosus is also known to be of benefit to dogs, as is saccharomyces boulardii.

The ecosystem found in the gut is key to health; from maintaining a healthy barrier against parasites and pathogens, to modulating the immune response and associated inflammation; not surprisingly this can then affect respiratory health. The microbiome also plays a major role in brain development and subsequent behaviour and mood.

Nutrition and the environment, including stress can all affect the distribution of bugs in the gut, along with antibiotics which by definition are anti-life. Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that provide health benefits to the host. They do this through a range of mechanisms including modifying the gut microbiota, competing with other species by creating a hostile environment, strengthening the epithelial barrier, and modulating the immune system. Whilst the jury is still out on some proposals, it is clear, that probiotics are of benefit when appropriate strains are selected.

Care needs to be taken when giving probiotics and dependent on presenting symptoms and disease, some strains and certain types of bacteria (fermented or soil for example), probiotics can have a negative impact on dogs, as well as a wonderful one.

If your dog has digestive issues, IBS, IBD, anxiety and any inflammatory or autoimmune disease, then check out our consultation services here.

Thanks for reading

Lisa x